So-called “the most disturbing film in cinema history” Srpski Film’s screenwriter Aleksandar Radivojevic, spoke to SineBlog for the first time in Turkey and analyzed the film which he describes as “post-Yugoslavia pornoir” in global-political and artistic dimensions.

– Everyone in Turkey who watched the film is curious about your “mind-set” as the writer and the director Srdjan Spasojevic (!). Are you “crazy”(!) or “brave”? What is the difference between the two for you? ?

Well, maybe I’m crazy, but I still consider myself to be one of the most normal people I know (!). Perhaps the outrageousness in the perception of the film comes from my deeply rooted belief that in the context of creativity, in terms of fiction, or art, nothing you can show should be forbidden, and everything should be permitted, if it helps you prove a certain point you’re aiming for. It seems to me that that belief of mine is not shared by many, especially in relatively recent times. General movie audiences nowadays have obviously forgotten what Cinema used to stand for, and what it used to contain during the 70s and 80s, or even 90s. They have been successfully pampered by mainstream studio films, but also the mainstream festival offerings in terms of what kind of content they should expect. That content is extremely limited now, its thematic and aesthetic boundaries clearly drawn by the standards of political correctness that dictates the ratings, and therefore the level of its market exposure. Any content that doesn’t fit these standards is considered to be “crazy” or “brave” now. So, before you embark on a filmmaking journey today, you should ask yourself are you brave enough to be crazy, or are you crazy enough to be brave?

– Contrary to many people, I consider Sırpski Film as a very political film, literally “a pessimist post-Yugoslavia syndrome film”. Do you agree with that? Can you explain your views as the screenplay writer? And how do you describe the “genre” of the film?

It is a very political film indeed, in the sense Pakula’s The Parallax View, or Pasolini’s Salo are political – it may also be a combination of these two films in terms of genre itself – brooding neonoir-conspiracy thriller and a grotesque, horrific De Sadian nightmare satire. Considering how pornography is structurally used as a binding tissue for all these elements, I think the most adequate genre brand for it would be PORNOIR. You can add a pinch of Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (which is my own personal all-time favorite) to it, as the pattern for the psychological aspect that goes with the political here.

Concerning “post-Yugoslavia syndrome”, you are absolutely right. As a country, we are still struggling to survive through the extreme post-traumatic stress disorder induced by the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, which is the insurmountable illness that all other ex-YU republics are experiencing too. There is no direct mention of Yugoslavia in A Serbian Film, but it certainly hovers above it like a restless spirit, a “lost paradise” in whose post-apocalyptic ruins its characters cohabitate. We are all living in the estranged parts of a dismembered whole. That fact alone is governing our existence, and our confused state of mind, as we are trying to patch our collective identities up and adapt to our unfortunate condition, before we totally disintegrate or self-destruct, both socially and economically. All the inherent pessimism and melancholia present in the film stems from that not-so-simple fact most of us are still unable to successfully grasp.

– Maybe it’s a classic question that has been asked a lot, but what made you feel compelled to use such hard-to-digest metaphors to convey your message?

When you are trying to prove an extreme point most people are ignorant about, you need to do it with extreme means. Nowadays, when you want someone to listen, you can’t just tap him on the shoulder anymore, you need to hit him in the head with a hammer. I’m a firm believer in that kind of strategy in general, but it’s also a matter of genre. When you’re making a contemporary satirical horror noir bordering on pornography, you need to make it really horrific and intimidating in order for it to work. You shouldn’t rely on tired genre tropes, you need to show something that hasn’t been seen before.

Probably the “hardest-to-digest metaphor” you are referring to is “newborn-porn”- but to us, it was definitely not a case of “let’s think of the most vile and disgusting thing ever”, and you wouldn’t want to see what we’d come up with if we really did. It was simply the most exact and precise illustration of the unpleasant and disturbing national predicament our state and its population have found itself in. It specifically speaks to our own generation – as soon as you are born, you are immediately “fucked”, deprived of your future by the powers that be, using you as cannon fodder in their mindless bloody wars, and countless other murky agendas, all under the guise of “national interest”. On top of all that, the oppressive authorities that are systematically abusing you, are themselves being controlled and manipulated by yet another, even greater oppressive force from the outside, the one that identifies itself as “humanitarian” and “globalist”. It basically controls everything – your politics, your economy and your culture, the films you make. These films are supposed to paint a singular picture of how that higher authority sees you, its victim, and how it wants others to see you as. So, they are dictated to be aesthetically inept, creatively bankrupt, pathetic, saccharine little stories about impoverished, mentally incapacitated peasants living at the outskirts of the European third world. It all sounds very Burroughsian, doesn’t it? It is our own national “Naked Lunch”, but it is also our reality. We’ve been living it for the past three decades.

– The name of the movie is “A Serbian Film”, but do you think that; considering exploitation, violence and wars are all over the world; it is actually a highly universal movie? For example, does every violence around the world “starts (and ends) with the little ones”?

Its themes and its meaning were always meant to be universal. The entire world population is living under the domain of the particularly aggressive strain of global capitalism. Exploitation, violence and wars are all unfortunate byproducts of its reign, tools of its trade. Serbia is just this god-forsaken, peripheral region of it, where its hold and its effects are most bluntly visible. When you strip down this omnipresent, inherently corrupt political system that governs liberal capitalism to its bare essentials, it’s very similar to violent pornography. The oppression that this system generates is the same kind of oppression that operates in a shady porn underground. Pornography here is simply a metaphor for life, life itself, modern life. Life in Serbia, and life in the rest of the world, in the other “unfortunate” countries. Once you enter this raging liberal capitalist machine, you jump into the meat-grinder, the endless cycle of your own exploitation. As all exploitation, it always starts with the little ones, and then moves onto the bigger prey.

– I just stated that I found the movie pessimistic. Now, 10 years later, do you think the situation is still bad in Serbia and in the world? Is there nothing to do?

Still bad? As you can see for yourself, it’s even worse. A Serbian Film was frequently misunderstood ten years ago when it came out. But when you take a look at the world now, through its globally disastrous political climate, you have to be a pathological optimist to say that our film still seems so “out there” and unreasonably brutal or pessimistic. Actually, through its rapid regression into social and political chaos, polarization and turmoil, the rest of the “civilized” world is becoming to look more and more like Serbia now, gleaming illusion of its democracy gradually stripped down and evaporating. Ironically, through the three decades of our constant degradation, we have actually become “progressive” in our own downfall. We are an aberrant socio-political avant-garde now, our unfortunate fate prophetic to the rest of the world. Look in the mirror closely, we are what you are turning into, your future. You have being downgraded to our status. Unexpectedly, Serbia has gone global, and not the other way around!

– Would you change any things if you were writing the script now? If yes, which things for example?

I always think in the context of what is right for the film, for the story you’re telling, the world you’re creating. So there is no calculation on my part in terms of harshness, or how far you’re willing to go, only what is most appropriate for the point you’re trying to make. I wouldn’t change much in the hindsight, maybe a few technical things to add, few character details here and there, but nothing too spectacular.

– In my opinion, it was clear that the well-known controversial scenes in Srpski Film were highly stylized and unrealistic. But the overwhelming majority is stuck in those scenes. Do you think that the violence and adult content (“shock and awe”) in the movie made your message invisible? I always thought that perhaps you wanted to hit our face that we are apolitical people who get stuck in form but avoid interpreting the content. Was it your intention?

The entire film is intentionally stylized. It’s not realism, it’s a heightened cinematic reality, as it should be. Satire is exaggeration of the trivial in order to get the point across – life is porn, job is fucking etc. So, in terms of genre, when you’re dealing with noir horror satire, shock and awe are part of the language, and subtlety must go out the window. I have always wanted to make stylized, expressive, baroque films that transcend genre. On the other hand, social realism is a dominant genre in stately-funded Balkan Cinema, so we specifically wanted to avoid it. It is traditionally low on visual expression, and too one-note in its meaning, while it wallows in the pathetic. Perhaps if it was done in that style, people would take it more seriously, because that’s what they’re accustomed to, it’s how they’re trained to react to it. Documentary style automatically means something subtle and serious, while expressive thriller/horror genre vibe means exploitation. I think that’s fundamentally wrong. In fact, when they’re watching a genre film, audience spontaneously goes into an entertainment-prone trance, so they’re much more open to subversive ideas that you can slide into their subconscious. Robin Wood, great film theoretician wrote about that, but he was dealing with the 70s genre films, which were multilayered and provocative, contrary to the ones made now.

In that sense, you’re absolutely right – it’s not only that most people are inherently apolitical, but that contemporary cinema (both mainstream and arthouse) has rendered them unable to separate form from content. If they’re watching a genre film, it must be entertainment only, if it’s a documentary-style drama, its content must be serious. Our film was made to defy those false preconceptions.

– In an interview, you count your sources of cinematic inspiration as Post-Vietnam Syndrome filmmakers such as Roman Polanski, Brian De Palma, William Friedkin. What about the highly political cult films of Pier Paolo Pasolini like “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom”? What else inspired you, cinematically or not?

I don’t think De Palma’s films are any less political than Pasolini’s, even the majority of those he did at the peak of his Hollywood powers. It was only cleverly disguised by the genre, which is exactly what we were talking about, concerning form and content.

Yes, you can definitely say Salo is similar to our film conceptually, in terms of how far it goes with its satirical ferocity, I have mentioned it before. But in the terms of genre, I would put us closer to the noir-thriller-horror part of the equation. For example, take Schumacher’s 8mm – it surely turns into a pretty conventional Hollywood programmer in its second half, but what if it didn’t? What if its snuff production wasn’t just an isolated job for hire, but a serious, stately funded production ring? What if it went much further, deeper into this underground pit of depravity, with Nicolas Cage character going undercover as a production assistant, or a fake backer, and getting really involved in it, then unable to get out? That’s exactly the film I wanted to see, the one I imagined when I first seen the trailer, knowing Se7en screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker was penning it. Instead, we got that watered down version, but A Serbian Film is much closer to the right incarnation of it, the one I have seen in my head back then. Our film is, in part, my vision of where American thriller should have gone as a genre at the end of the nineties, but unfortunately it went full steam ahead into the safe zone of politically correct, unadventurous fluff. Then 9-11 happened, and everything vital and interesting about the mainstream Hollywood Cinema was dead and gone, and it never recovered.

As for what other inspires me in the cinematic realm, Japanese filmmakers as Takashi Miike and Sion Sono are always there in the background, as well as South Korean cinema that does exactly what Hollywood should be doing, if it wasn’t already dead and buried beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center. The great, late Polish filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski, European Cinema’s still best kept secret should be given an honorary mention. Outside of cinematic influences, writers such as Ambrose Bierce, Theodore Roszak, James Ellroy and early Clive Barker will always be an inspiration. In the domain of graphic novels, writers as Grant Morrison ( The Invisibles, The Filth, Nameless), Garth Ennis ( Preacher, The Boys, Punisher ), and Warren Ellis (Transmetropolitan) are the true visionaries that will, in the times to come, be endlessly adapted and ripped-off on cable TV and all the Netflix’s and Amazon’s of the world, if everything goes well.

– I had read that you did not have much difficulty in forming the cast of the movie, you could get the well-known actors and actresses. But I think the post-production phase was very hard. What problems did you experience? And, in general, how hard it is to make a film in Serbia now?

Well, we were talking about the post-production in Germany, not in Serbia, believe it or not. Employees of the company that was hired to make a 35mm print of the film were scared shitless when they saw it, they thought it was the real snuff movie, and they contacted the local police. They wanted to arrest Srdjan, the director, for allegedly trying to blow up a real snuff film on 35mm, if you can believe that nonsense. It took him some time to explain to them that we used prosthetic dummies in the film and not real people, and that if he had really shot a genuine snuff, he surely wouldn’t be so dumb to try to make a 35mm print of it. It took some persuasion, but finally they agreed their story was too far-fetched and probably idiotic. The only catch was that now they demanded to destroy the finished 35mm print that was already paid for! And destroyed it was, in modern Germany, the European “bastion of democracy and freedom”, Srdjan couldn’t do anything to stop them. The running joke is that in Germany, burning films apparently never goes out of style.

Financing a film in Serbia is hard as it always was, as we are limited to state funding, and the State has always preferred spineless little art films without firm stylistic identity and real thematic edge to them, because otherwise someone might be offended. Situation improved a bit in the last few years, thanks to the changing of the guard at our governing film institution, so they have become more open to genre diversity and backing some fresh voices among local filmmakers instead of the same old “usual suspects” all the time. Still, it’s pretty far from a normal situation, as the state budget for culture is ridiculously low.

– After Srpski Film in which projects did you take part? I ask you this because your fans or haters(!) in Turkey are almost never heard your name after. And which projects do you have soon?

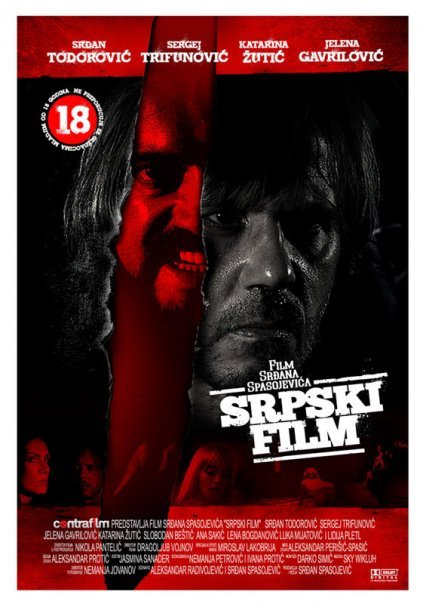

After all the international exposure and great popularity A Serbian Film attained, the decade after it was incredibly hard. In Serbia, it was almost universally hated and reviled, so we couldn’t dream of getting state funding for our next project, and without the state funding, potential foreign backers couldn’t do anything to help us. So on the one hand, you have master filmmaker William Friedkin himself praising our film while receiving his Lifetime Achievement Award at the Venice Film festival, talking how great it is, and how its haters should leave the hall and on the other hand you have officials in Serbia denying it completely. Srdjan went to the United States, trying to get our follow-up to A Serbian Film, WHEREOUT, off the ground, but nothing came of it. I have another satirical horror script where I got Marilyn Manson (who is a number one fan of A Serbian Film, also) playing God, and we found some backers in Belgium, but still no state support in Serbia.

Only few years back, with a talented director/FX supervisor Borisa Simovic, I have written a Fantasy-Western script about Nikola Tesla, LUMINOUS, that somehow managed to get state backing. It’s an international production that should go before the cameras next year, I hope. The same goes for another wild, satirical teenage comedy i have co-written recently.

Finally, I got backing for a half-hour short IN TOUCH, a contemporary sci-fi horror fable that will be my directorial debut. It is a more lyrical expansion of the themes seen in A Serbian Film, and it is almost done.

– I want to end with a “paparazzi magazine” question: why the director Srdjan Spasojevic is not in social media?

Srdjan is an idiosyncratic, old-school character, not unlike his idols, Clint Eastwood and Chuck Norris. He despises anything social, he spits on media and chews it out. But he’s very friendly if you meet him in person.